Poverty Is a Moral Problem

|

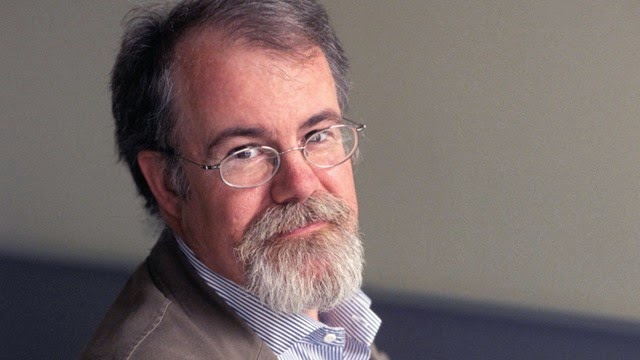

| Development economist William Easterly says too much aid undermines the rights of the poor. |

William Easterly, professor of economics at New York University, is one of the most prominent iconoclasts in the field of international aid. In 2006 he published White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. Kent Annan (Following Jesus Through the Eye of the Needle; After Shock) talked with him on a frigid Manhattan day over hot green tea the day after the launch of his new book, The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor (2014).

What are the "forgotten rights of the poor"?

The rights of the poor should be the same as the rights of the rich: the core, inalienable rights that started with the language of the Declaration of Independence, including the idea that governments exist by the consent of the governed.

There is an ongoing debate around the world between the advocates of freedom for the individual and the advocates for more authoritarian, powerful states like Russia and China, and seen in battles from Ukraine to Venezuela to Ethiopia.

The sad thing is that the field and practice of development have too often been on the wrong side of this debate. They've implicitly painted themselves into a corner where they're on the authoritarian side. Then they're backing the autocrats, backing the oppressors against the oppressed.

You are an economist, but this book seems to largely make a moral argument.

As an economist, to include such a strong moral dimension is a bit unusual. I start the book making it clear that the idea we can have a purely technical approach to resolving the problems of poverty without any moral implications is an illusion.

For me, this has been a long intellectual journey, from being one of the experts who was oblivious to the "rights of the poor" issue, to now criticizing those experts. In my development career, I worked closely at various times with autocratic governments and officials in places like Mexico and Russia and Pakistan, and in Africa with Ethiopia and Ghana before it was democratic.

I realized our attitude towards the poor is so often condescending and paternalistic. We think of them as helpless individuals. We don't respect their dignity as individuals.

The next step was not to just avoid paternalism or condescension but actually to go back to first principles and think about the rights of the poor and what role those rights play in development. Economists' research actually does give the institutions associated with individual rights a lot of the credit for the development in the West and the rest of the world. This combined with my own moral awakening that these rights are a desirable good in and of themselves. Whenever we violate them, we set back development.

Humility or self-restraint seems to be a theme through your work.

My cultural and faith upbringing contributed to the feeling of humility. I grew up in the Midwest, in Ohio, with a faith background that stressed humility, not being over-confident in your own wisdom, not being too self-important. That informs my openness to a critique of experts as being too arrogant in their own knowledge and too oblivious to the moral consequences of their overconfidence that can lead to doing damage to other people.

For example, if you work with the government of Ethiopia, you have to consider whether you may be indirectly contributing to someone being kept in jail for 18 years like Eskinder Nega, a peaceful blogger who made quite innocuous criticisms of the government.

http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2014/april-web-only/poverty-is-moral-problem.html

Comments

Post a Comment